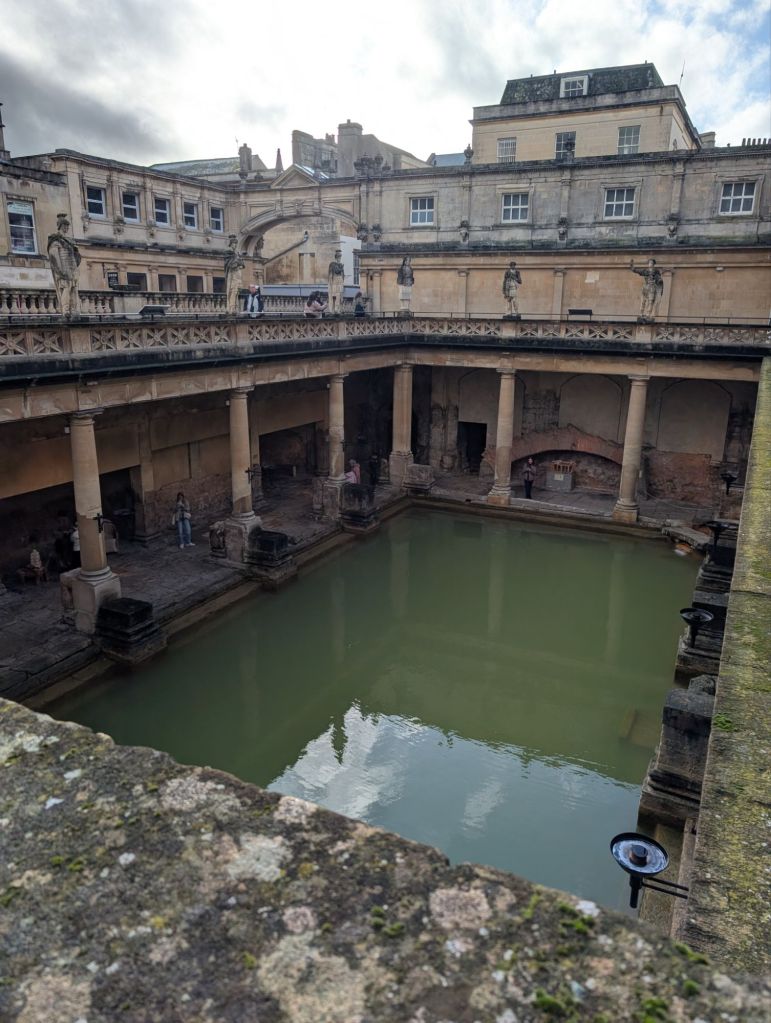

As early as the 1870s, Pylant Springs served as a summer resort for pleasure seekers and patients alike as part of the renewed interest in water cures, or hydrotherapy. Therapeutic use of water dates back as early as 1000 B.C., and Hippocrates discussed these treatments in On Air, Waters, and Places, writing that “there are certain constitutions and diseases with which such waters agree when drunk.” Bathing has remained a staple of health and relaxation throughout the centuries, spreading across all cultures.

In the 18th century, Empiricists who put emphasis on sensory experiences revitalized this idea, sparking a renewed interest in water treatment and resorts that focused on health and relaxation. Tennessee, with its plentiful natural water sources, was a perfect fit for this industry. The small town of Tullahoma, roughly 70 miles south of Nashville, quickly made a name for itself for Hurricane Springs and Pylant Springs, both famous for their “green water.”

Pylant Springs was already an established summer resort by 1875, when the owners formed a Board of Directors to create improvements and management for the springs, according to a notice published in the Nashville Banner. It soon became a regular resort destination for Tennesseans, even hosting an 1883 reunion of soldiers who had served under the command of Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest during the Civil War.

Visitors would arrive in Tullahoma via the Nashville, Chattanooga, & St. Louis Railroad. It was sixty-nine miles from Nashville towards Chattanooga. They would then take a hack (horse cart) to complete the six mile journey to Pylant Springs.

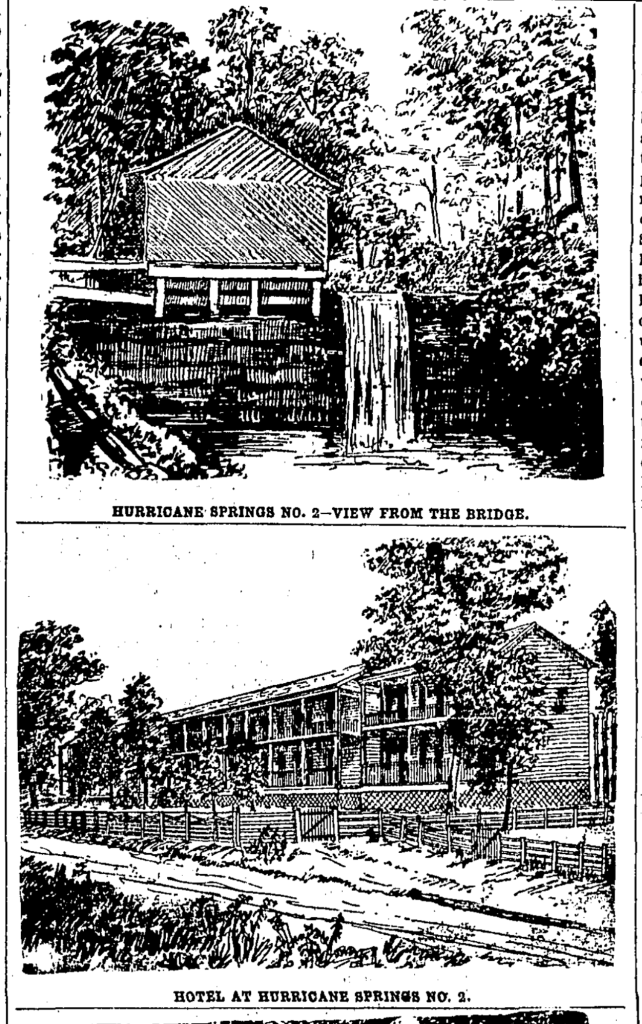

Over the years, the property would be sold and transferred, and many would try to make new names to reignite interest in the property. Pylant Springs has been called Hurricane Springs No. 2, Cascade Springs, Mountain Falls Springs, and even Pilot Springs throughout the years — but more on that, later.

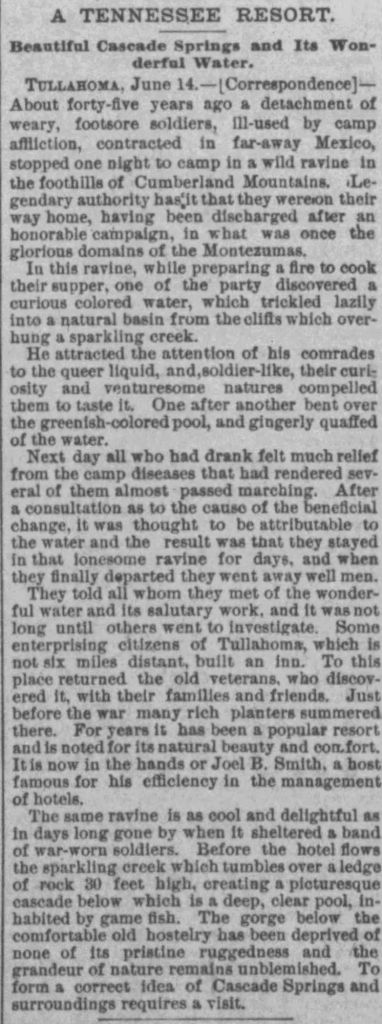

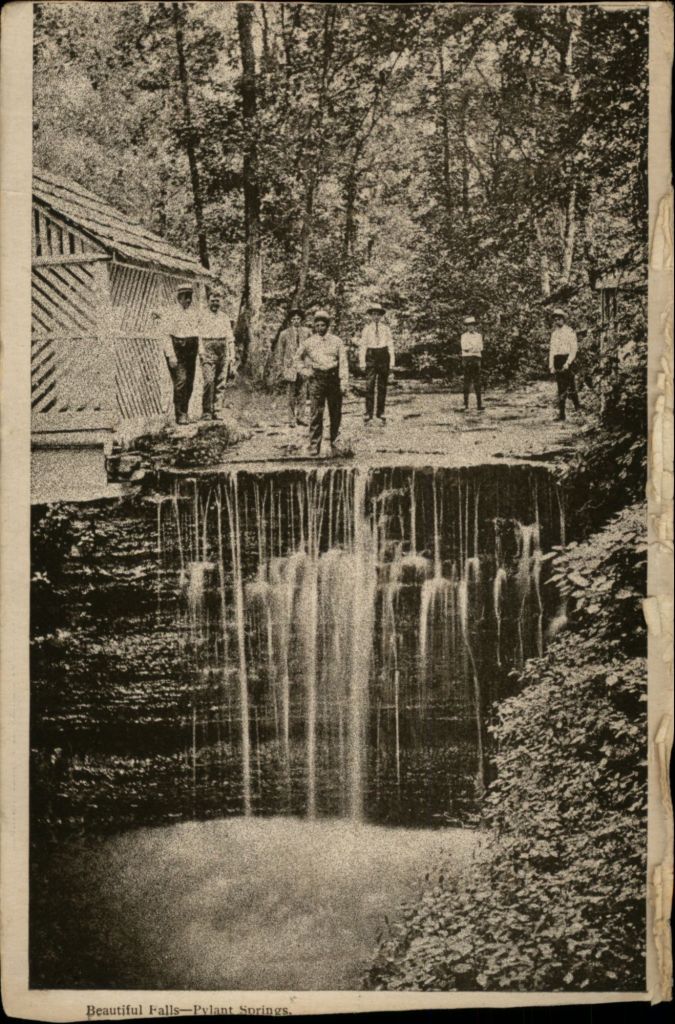

By 1883, Pylant Springs was well-established and could now host about 100 guests. An article in the Nashville Banner (advertising the resort as Cascade Springs) described the property as follows:

A meandering stream, fed by two mammoth free-stone springs of the clearest and coldest water, passes through the grounds. Follow this stream but a short distance, in sight of the hotel, and a most beautiful cascade comes into view, over which the crystal waters fall from the rocky cliff to a cove of picturesque grandeur. Further on another waterfall is seen, equally as attractive as the first. The glen or cove referred to seems to be rich in springs, and how many varieties will be discovered remains yet to be seen.

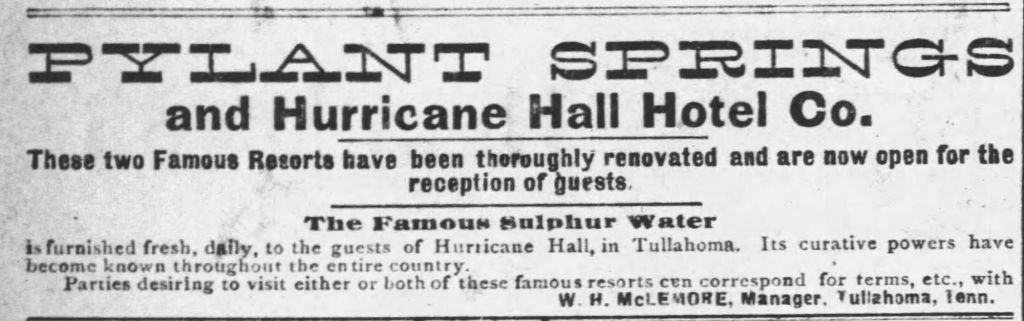

The two Tullahoma resorts of Hurricane and Pylant were linked in the early years, before the ownership changed hands and management split between the two. However, advertisements for one usually mentioned the other as a way to raise awareness, especially as the waters shared similar properties. Briefly, in 1887, Pylant Springs became “Hurricane Springs No. 2.” According to an article in The Tennessean, monthly rates ranged from $25-55, weekly $10-15, and daily $2-2.50.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, newspapers regularly published the comings and goings of townspeople, as well as interesting tidbits. Visitors to Pylant Springs were often listed in the paper, as well as a few interesting stories. In 1883, an article in the Clarksville Weekly Chronicle described a young girl who was taken with a parrot she had seen at the resort. When trying to convince her father to buy her one, she argued: “You can teach it to curse.” An 1891 article described a man with impressive facial hair who lived on the Pylant Springs road: “His whiskers are full six feet long, and when combed out cover him completely.”

Advertising was essential when it came to managing summer resorts. Proprietors put classifieds in newspapers throughout the state, boasting of the healing properties and beautiful scenery of Pylant Springs. As an effort to build interest in the resort, an 1892 article created a mythology about the springs, claiming that soldiers in the Mexican-American war sought refuge there in 1847.

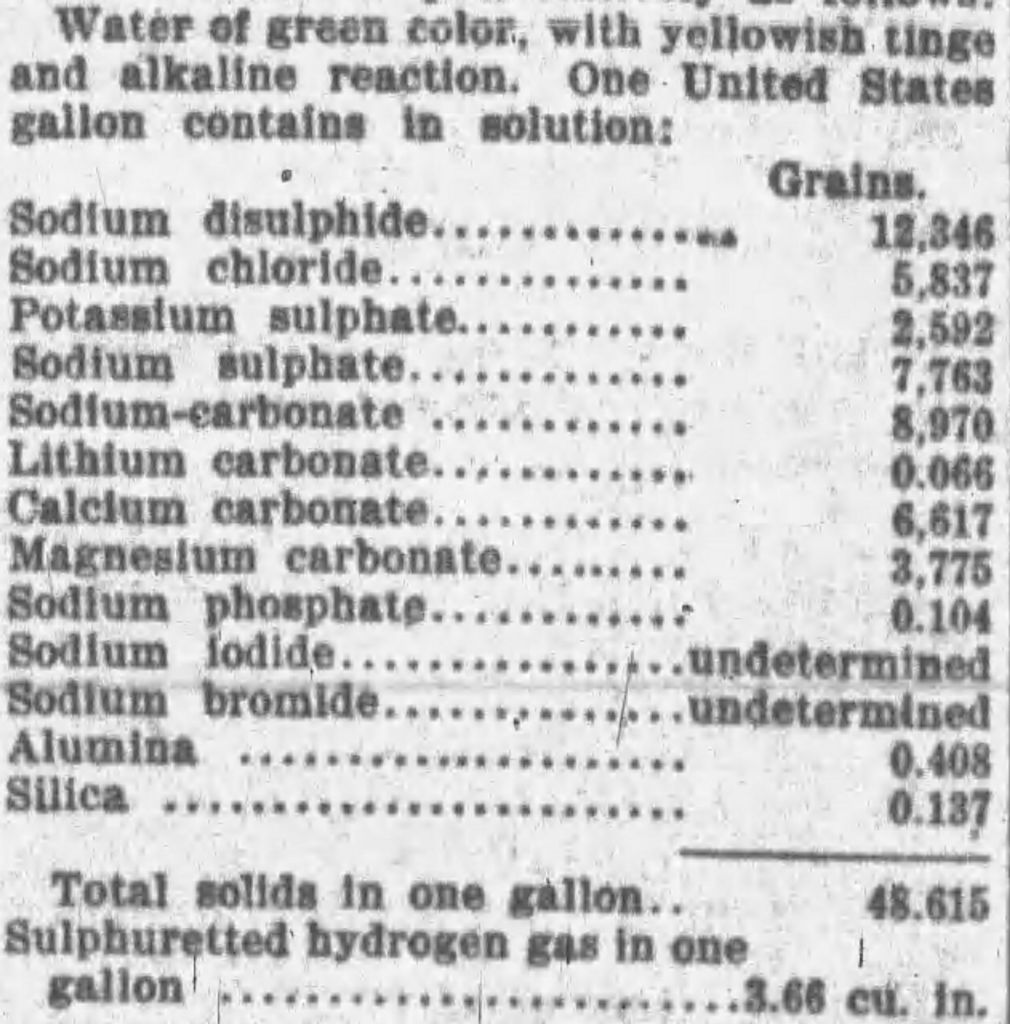

Health claims for Pylant Spring focused on the “green water” found there. An 1897 article in The Nashville Banner claimed the water never failed to cure “that dread disease, gallstone.” The water was bottled and sold nationwide, but the advertisements assured people the best cure was only to be found in person at the resort. The source of the sulphur was the Black Devonian Shale abundant in the waters.

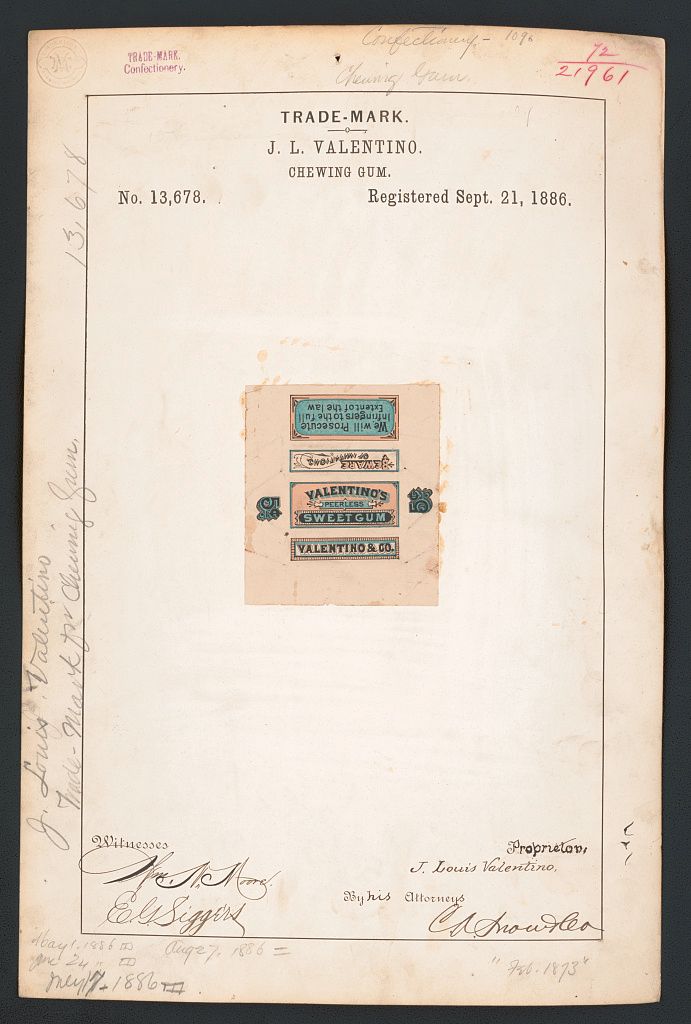

In the late years of the 1890s, business at the resort slowed down. Allegedly there was a fire at the hotel in 1900, but a 1905 article mentioning the reopening makes no mention of this event. Leading the effort to reopen the resort was the Mountain Falls Spring Hotel Company, recently incorporated to run Pylant Springs (to be briefly renamed Mountain Falls Springs). The man in charge was named J. L. Valentino, a Nashville businessman already known for his successful chewing gum manufacturing.

From 1905 to 1908, advertisements for Pylant Springs (briefly Mountain Falls Springs) were extensive. Multiple long articles celebrated the resort’s beautiful scenery, hotel accomodations (now with toilets!), and healing waters. Improvements were extensive, with apparently a new lake planned for fishing. Roads allowed for easier travel between Pylant Springs and Tullahoma, meaning it became easier for guests to arrive at the resort.

Unfortunately, the ease of travel with automobiles did not necessarily lead to continued success at resorts such as these. As infrastructure improved, people had the ability to travel to more destinations than ever before. It was difficult for an aging resort in a small town to keep up with the accommodations offered at other places like Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga, for example.

Pylant Springs was a seasonal resort, usually only operating in the summer. When the hotel burned down in August 1925, only the caretaker and his family were on the property. The hotel was never rebuilt.

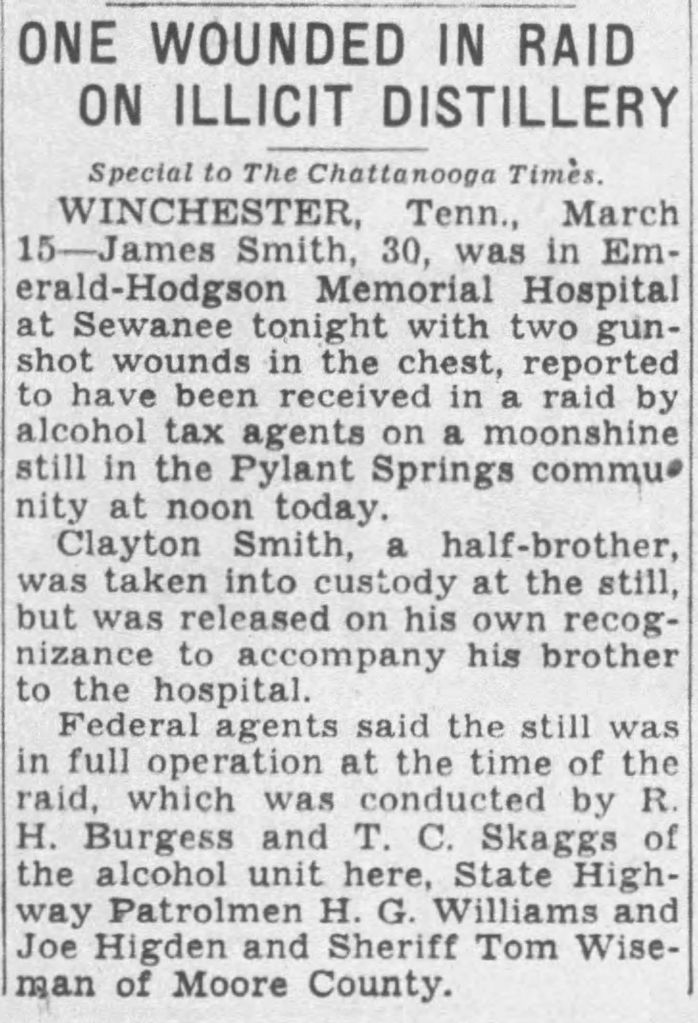

Pylant Springs is located in the community of Awalt, also known as Mash Bread in its early years. This area was well-known for its moonshining business:

“[T]he springs of Awalt also provided the ideal spot for the construction of whiskey stills. At one time, Awalt was noted for the moonshines. During the 1920s ‘illegal liquor’ was made in almost every hollow around the community and it seemed to be the major industry of Awalt.”

– Anna Trawick, Awalt: A Nostalgic Memory and Farewell, p. 9. from the Franklin County Historical Review, Vol I, No. 2

The demand for moonshine skyrocketed during the Prohibition period following the 18th amendment passed in 1919. Moonshine requires fresh spring water, and with the resort no longer on the property, Pylant Springs with its plentiful green water was an appealing site for moonshiners. It’s unknown how much moonshine was manufactured there, but in 1948, a man was shot during a raid on an illicit distillery in Pylant Springs.

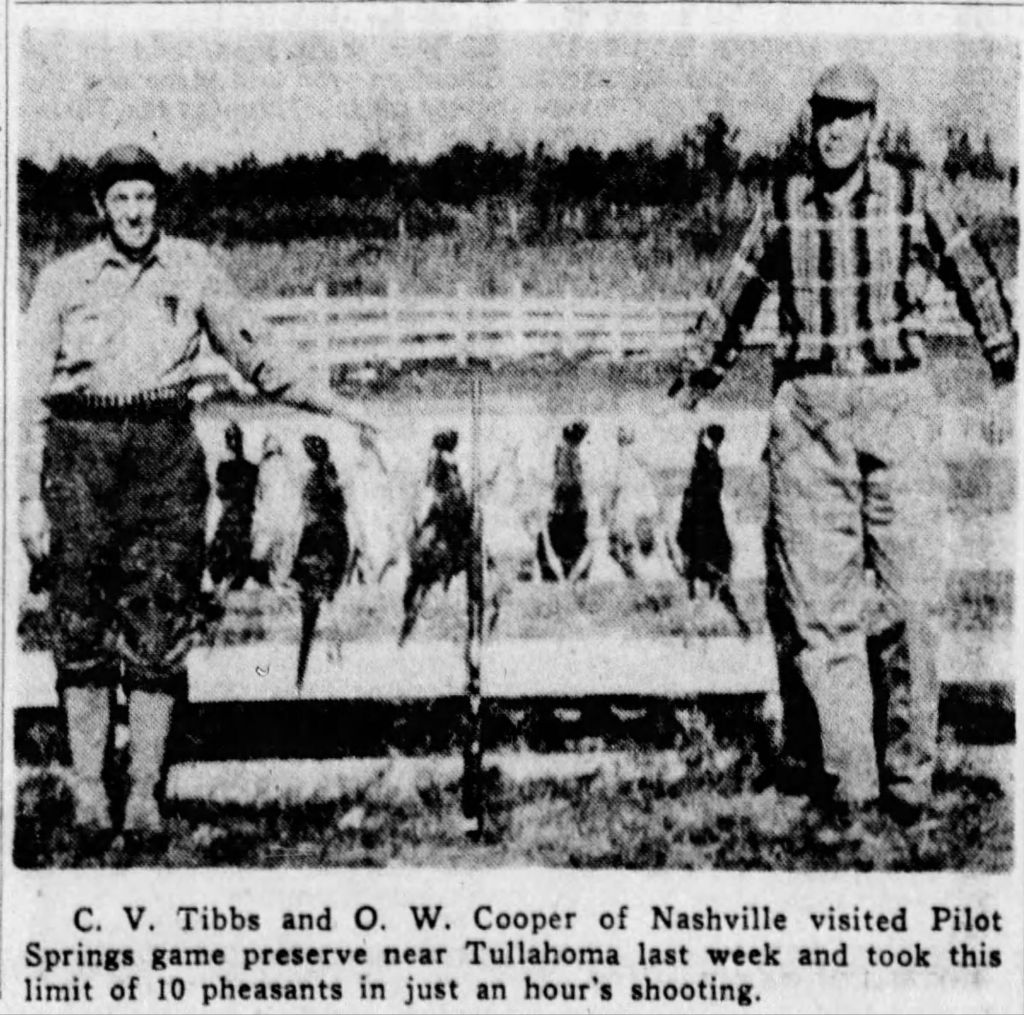

40 years after the hotel burned, there weren’t many people who remembered spending summers at the resort in Pylant Springs. In fact, a decades-long game of telephone meant that the community was instead remembered as Pilot Springs. In the 1960s, a hunting game preserve was established on the property. For $20 a day, hunters could come to Pilot Springs and hunt pheasant, quail, and partridges. A hunting lodge was eventually built to serve as accomodations.

It’s unclear how long the hunting lodge remained open. Over the decades, whatever property remained at Pylant Springs became a hazard and was eventually torn down. Occasionally, one might find remnants of the old sites in the waters that flow through the property, such as old hotel keys, dishware, and even brickwork.

In the 1990s, the property was purchased by a local doctor who built his home there. It remains a pleasant oasis and refuge from the busy life of the city. Its beautiful spring water remains a source of good health — even if it doesn’t necessarily cure an extensive list of diseases as once claimed in the 19th century.

There’s but one Pylant Springs on earth – it’s the only water that cures.

– 1905 advertisement in The Tennesseean